Introduction

why was this de-identification framework created?

At a foundational level, leveraging better care and more sustainable service system operations through secondary use of health data is all about relationships – between typically large/complex linked arrays of person-level data, and those statistically/methodologically well-equipped parties, often found in academic settings, who have the capacity to transform the data into useful information products. Stated in slightly different terms: the presentation is concerned with the challenges around de-identification of complex, high-dimensional bodies of health data to enable appropriately privacy-preserving disclosure of the data to statisticians/researchers – while preserving the analytical integrity of the data disclosed.

What makes disclosure of health data for secondary use challenging?

Over and above the obvious challenges associated with data lineage – clinical service data originate within clinical systems in personally identified form – there are additional challenges that may substantially impede efforts to render the data in a form that meets the requirements of data access adjudicators:

- Legislation, regulations –

- Data required to paint a minimally complete picture of a “patient journey” are likely to be held by a diverse array of parties who are subject to different governance structures and bodies of legislation (e.g, PIPA for primary care providers; FIPPA for health authorities);

- Legislation, regulations or framework/guideline documents almost invariably fail to provide operational definitions of key constructs such as “de-identified” or “anonymized”.

- To meet legislated/regulatory/ethical obligations, data access adjudicators must navigate through an array of possible approaches, but the sources of those obligations do not address the key question of which type or level of de-identification is required for a given disclosure.

- Data required to paint a minimally complete picture of a “patient journey” are likely to be held by a diverse array of parties who are subject to different governance structures and bodies of legislation (e.g, PIPA for primary care providers; FIPPA for health authorities);

- Existing de-identification methodologies “work” for datasets that contain small numbers of demographic features (e.g., date of birth, postal code) and a very circumscribed set of clinical attributes, e.g., a single diagnosis made at a single point in time in a single setting. However, they do not scale out to the typical datasets required from source clinical information systems to optimize point-of-service care delivery processes or service system operations or planning or performance monitoring – see Moselle, Robertson & Koval (2019).

- Parties with custody and control of health data will typically need to cast a broad cross-jurisdictional net to find the diverse array of parties who possess combinations of clinical domain knowledge and up-to-date “data scientific” expertise. Processes that ‘work” for internal uses of data by within-jurisdiction employees for purposes of quality assurance/quality improvement are not sufficient.

All of the factors point to a need for cleanly and clearly articulated procedures that “understand” legislated/regulatory/policy obligations, as well as complex, high-dimensional health service data. As well, the methodology must grasp at a deep technical level the statistical basis of procedures required to meet those obligations – and demonstrate that obligations have been fulfilled. Further, the procedures must also understand the need to preserve the analytical integrity of the de-identified data. If the statistically-derived products are going to be fit for purpose, the data must be fit for analysis.

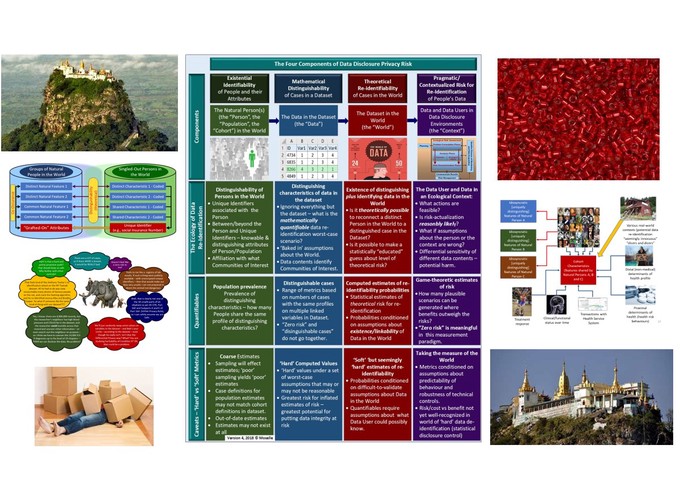

What is contained in the framework set out in the powerpoint?

- Slides #12 - 14 – summary view of data disclosure privacy risk model – this provides the basis for everything else contained in the presentation. It provides a context for operational definitions of key terms such as “de-identified” or “risk”.

- Slide #5 – data de-identification options – forming a rough hierarchy – the framework must adjudicate among these options, in keeping with various obligations related to a given data disclosure.

- Slides #6-9 – limitations associated with common data de-identification approaches.

- Slides #17-20 – what are the components of “me” in “my data”? The distinction between “me” as a distinct individual and “me” as an exemplar of the properties of a cohort.

- Slides #21, 22 – the de-identification challenge – how to mask “me” but retain my generic properties.

- Slides #23, 24 – Component #1 of the model – identifiability of people and their attributes “in the world”.

- Slides #25, 26 – Component #2 – distinguishability of cases in the dataset – mathematical risk, i.e., statistical disclosure control-based definition of “risk”.

- Slides #28, 29 – Component #3 – re-identifiability of distinguished cases in the dataset.

- Slides #30 – 32 – Component #4 – the “being reasonable” component – what do we mean by “pragmatic/contextualized risk”; game-theoretic definition of “risk”; when does “zero risk” make sense?

- Slides 33, 34 – next steps – need for detailed standard operating procedures to operationalize and document each of the four components.

- [Not included in powerpoint] but is available on request] – framework for characterizing data disclosure scenarios – to be used to “stress test” a candidate data disclosure/de-identification methodology and determine where/how it might apply.

Possible next steps

- Constitute a group with appropriate skills/knowledge to evaluate the model.

- Generate a working set of data disclosure scenarios, spanning community, health authority and ministry data sources.

- Specify detailed standard operating procedures, generate working versions of template forms to document the results of the operations, provide benchmarks for evaluating measures of risk.

- Work through the standard operating procedures with a privacy-risk-challenging but representative set of data contents, including primary care data (e.g., MSP billing data with diagnoses); Health Authority data (including full cross-continuum encounter data and a subset of orders, e.g,. for medications); Ministry of Health data (e.g., pharmacy data). Document the processes and products with the forms associated with each component of the de-identification model.